To some people, the word “Patagonia” is just the name of an outdoor clothing company that makes expensive jackets and colourful urban wear. To others, the word conjures images of a mystical, far-off place filled with rock walls, pristine glaciers, and majestic condors. Gregor and I actually didn’t know where Patagonia was before we entered Argentina. All we knew was that if we kept on driving, we’d eventually get there.

Where in the World is Patagonia?

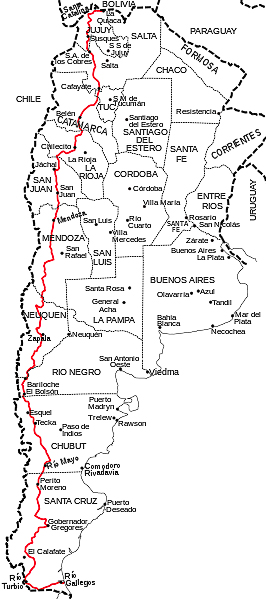

When we finally Googled a map of Patagonia, we were surprised by its size. It’s a massive region that occupies the southern part of South America and straddles both Chile and Argentina. It touches the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, and includes the Andes mountains in the west and the deserts, steppes, and grasslands to the east.

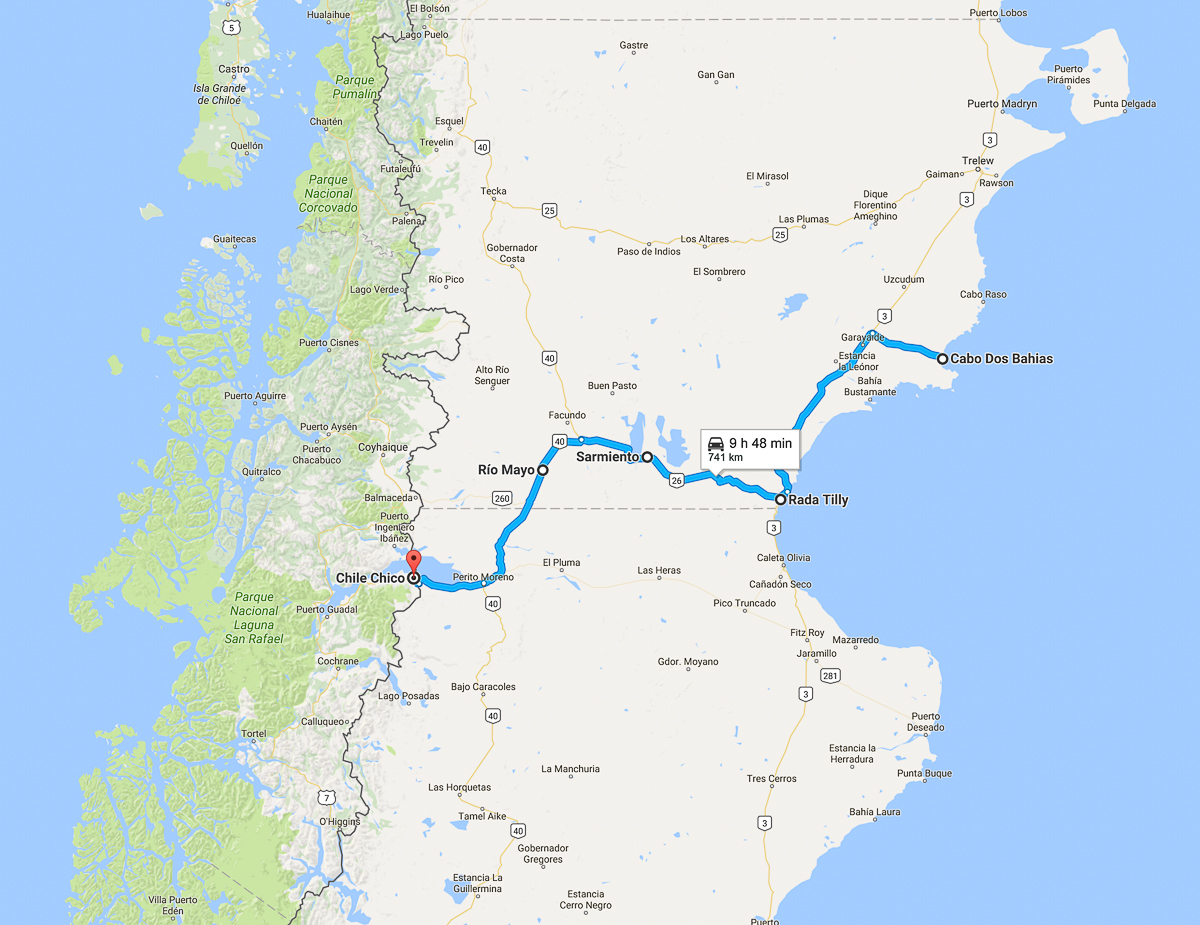

If you visit any website showcasing Patagonia’s attractions, you’ll see breathtaking photos of glacial fjords, lakes surrounded by snow-capped peaks, and coastlines teaming with penguins and whales. Having already seen the whales and penguins in the east, we were ready to see the glaciers, lakes, and peaks in the west. But first, we had to drive through the plains in between.

From the Atlantic coast, we drove westward through dry, steppe-like plains covered in grasses and shrubs. This type of terrain is called the Patagonian Steppe, and it goes on for what seems to be forever. Anyone who has driven through the flat monotony of the Canadian prairies can relate to what it’s like to drive in the Patagonian Steppe – the super-straight roads with few distractions, the long driving hours between gas stations – it’s as boring as porridge.

A Mighty Wind

One major difference between the Canadian prairies and the Patagonian Steppe is the wind. The damn Patagonian wind. It’s not uncommon for winds to blow at 80-90 km/h, and in some parts of Patagonia they can reach up to 120 km/h. The steppe is mostly treeless, so the wind here is relentless.

The wind can be so strong that you can barely walk in it. The wind gusts can be so abrupt that you can barely control your direction. Now imagine you’re driving a brick on wheels through this gusty wind, being buffeted from side to side. Add a bit of oncoming traffic and suddenly the “boring drive” through the plains turns into a “boring drive interrupted by moments of terror”. These conditions are so exhausting that we couldn’t handle any more than 5 hours of driving in one day.

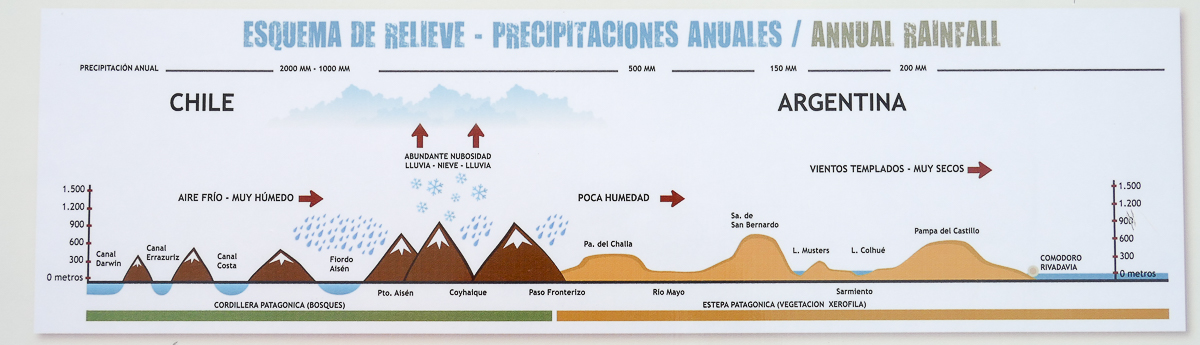

Apparently, Patagonia is so windy because there aren’t any mountains to stop the polar winds from raging across the region. The reason it’s so dry here is because of the rain shadow effect: the prevailing westerly winds from the Pacific lose their moisture on the Chilean side of the Andes, causing dry winds to descend on the Argentine side.

Not many people live in Patagonia’s windy plains. However, there’s a shocking number of sheep here, thanks to a sheep farming boom in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Occasionally we saw other animals such as horses, guanacos, and rheas (flightless ostrich-like birds). The rhea is especially tough to spot because it’s the same shape and colour as the shrubs on the steppe.

Sarmiento Petrified Forest

On our way to the Chilean border, we stopped at a Petrified Forest near the town of Sarmiento. Neither Gregor nor I had ever seen a petrified forest before, and we figured it would be a nice way to break up our long driving day across the plains. Sarmiento Petrified Forest is a Provincial Natural Monument so the admission (at the time) was free. We thought the fossilized wood and the interpretive trails were super interesting – well worth the stop.

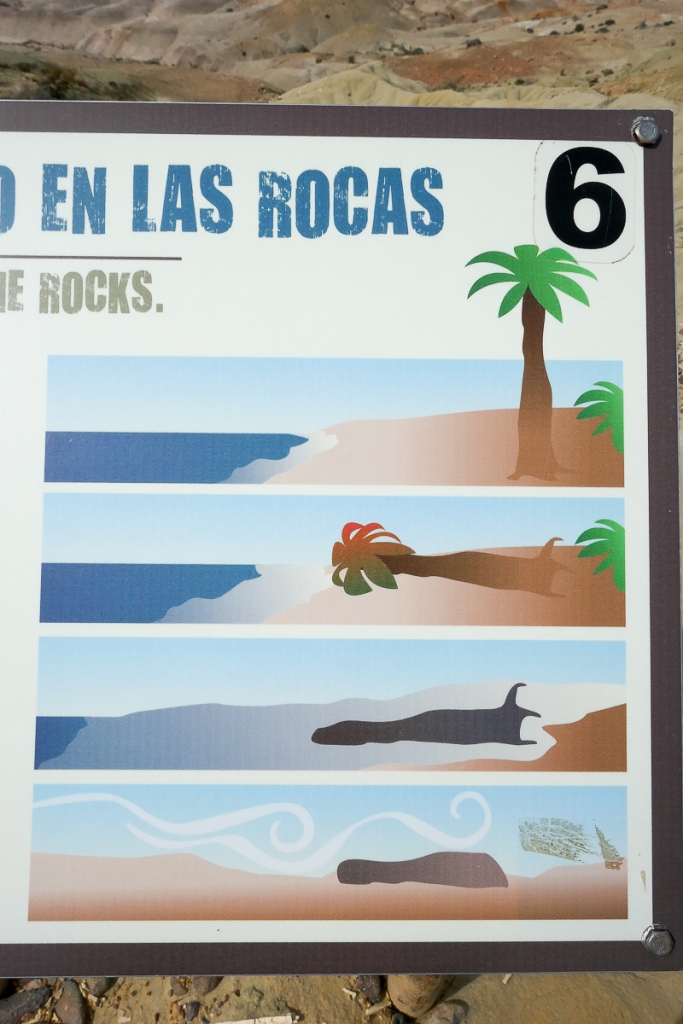

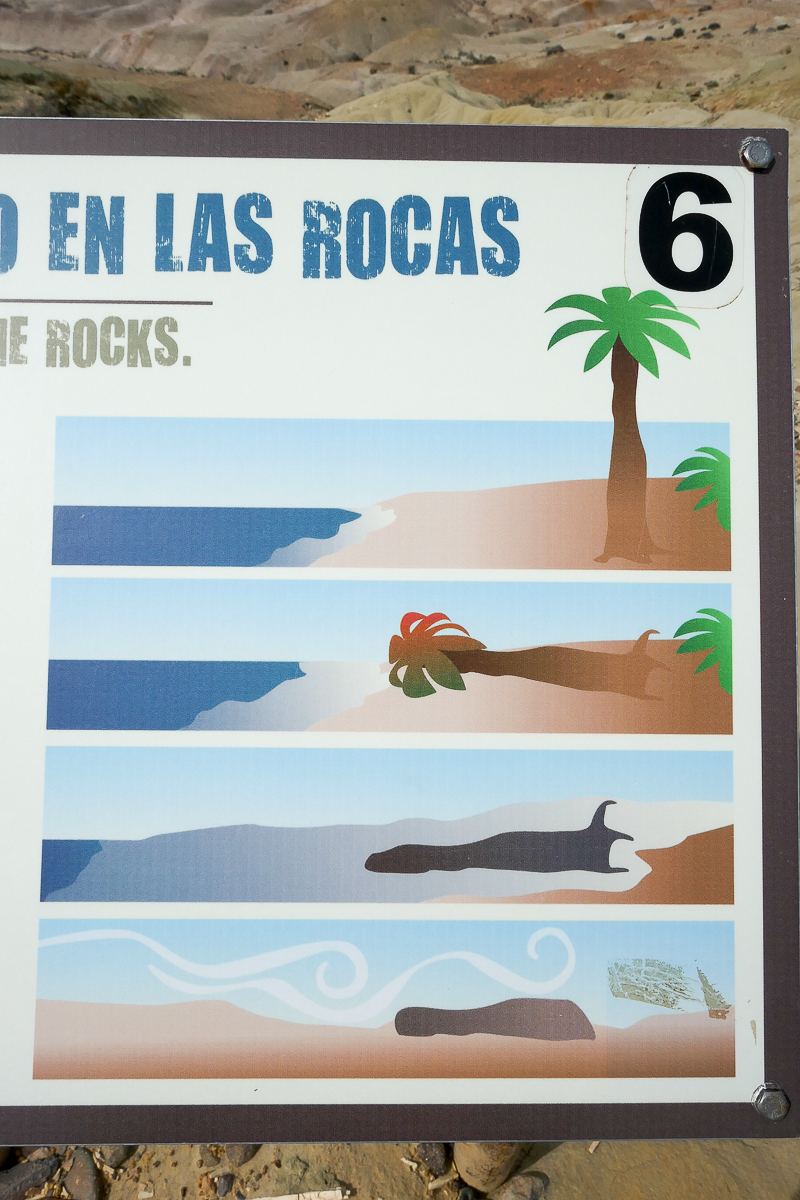

This ancient forest of palm trees and conifers became fossilized over the course of millions of years. When the Andes rose and blocked humidity from the Pacific, the trees started to die. The fallen trees then became submerged in flooded river waters. After nearby volcanos blanketed the area in volcanic ash, the rapid burial prevented the organic material from decaying. Over time the dissolved ash in the surrounding groundwater replaced the organic material and formed petrified wood. This diagram shows how a petrified tree is formed:

Ruta 40

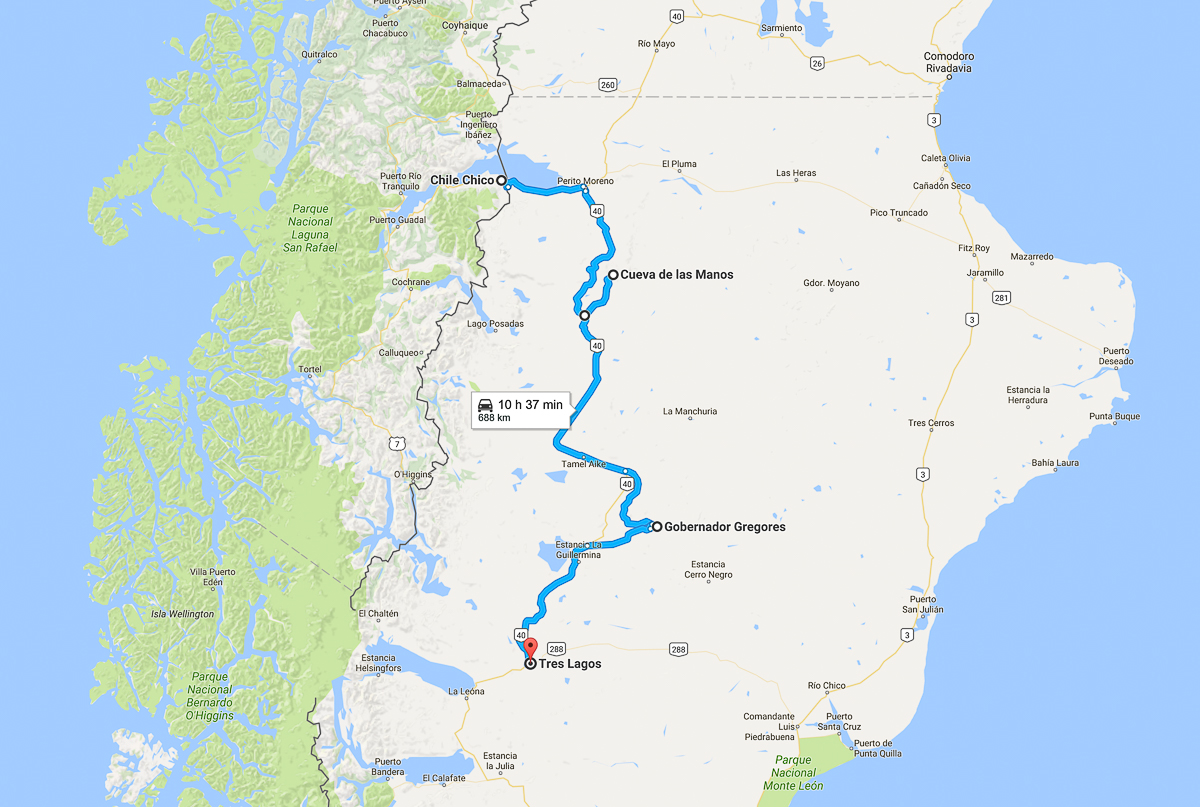

We entered Chile for a few weeks to access some fast Internet (3G speeds in Argentina suck!) and then returned to Argentina to drive the famous “Ruta 40” or National Route 40. This highway is one of the longest in the world, over 5000 km long. For comparison, the Trans-Canada highway is about 7800 km long and US Route 66 is 4000 km long.

We drove the southern part of this highway and it is very windy and desolate. Although most of our route was on well-paved highway, there were some maddening sections of gravel that stretched up to 70 km long.

It took us two long days to drive 700 km.

The gas stations are few and far apart on this stretch, and sometimes the stations run out of fuel. Since being stranded in bald-ass Patagonian prairie wasn’t exactly on our bucket list, we always carried an extra jerry can of gas and carefully monitored our fuel consumption (which was total crap due to headwinds). We planned all detours from Ruta 40 with caution.

Cueva de Las Manos

One detour we took was to Cueva de Las Manos (Cave of the Hands). It’s a Unesco World Heritage Site that preserves hand paintings created by nomadic people who hunted the guanaco.

Approaching the entrance to the Cueva de las Manos site

The paintings are on the walls of a wind-protected cliff and are over 9,000 years old. Made with natural dyes, the artwork includes images of hunting scenes, fertility symbols, human figures, and hundreds of hands.

Rather than placing their painted palms on the rock, these people blew paint around their hands to create a negative imprint. Pretty sophisticated for a hunter-gatherer! They picked a perfectly sheltered spot to practice their technique – I can only imagine what the walls would look like if the raging wind got a hold of the paint.

Similar hand paintings have been found on other rock walls in Patagonia within the migration path of the guanaco. Anthropologists believe that the nomads marked these walls with their hands to indicate their presence on these harsh plains, as if to say “I was here”. Walls with overlapping palm prints suggest that the same people returned to the site each year.

The sun was setting by the time we left Cueva de Las Manos, so we decided to wild camp at an abandoned air strip nearby. It was surprisingly protected from the wind and it was incredibly peaceful.

Ever since we entered the Patagonian plains, the driving distances between sights have been much longer and more demanding. It feels like we’re just going from point A to point B now, because there’s a whole lot of nothing in between. With the vast nothingness and the relentless wind, we think that the Patagonian plains is one of the most challenging places to drive in South America.

Boring as porridge?! Janice, clearly you have never had MY porridge (oatmeal is a much nicer word).

All joking aside, it was amazing how much the landscape reminded me of the Alberta Badlands. And the Cave of Hands was so cool!

Ted, I would love to try your porridge, I mean, “oatmeal”. Or should I say “haute meal”? Now that you mention it, the steppe is a lot like the badlands (minus the sheep). Thanks for reading!

Stellar reportage… as your many followers have come to expect. Dankeschön. (-:

Bitte schön 🙂 We’ve got excellent Internet access here in Buenos Aires so I can actually research the things we encountered along our travels. Makes writing a lot more pleasurable!